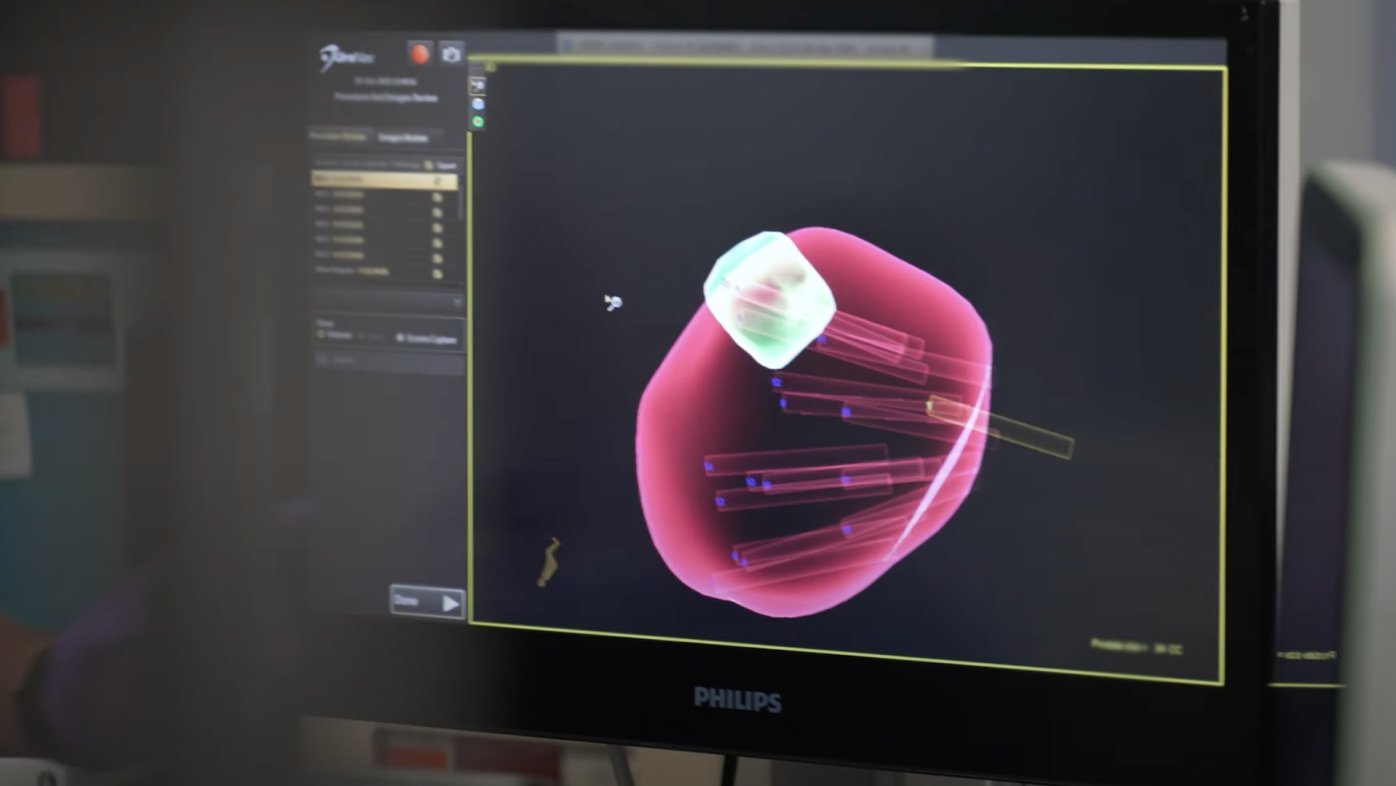

MRI guided prostate biopsy: A more accurate tool (video)

MRI guided prostate biopsy can provide a more accurate prostate cancer diagnosis to determine whether active surveillance or curative treatment is appropriate.

It was a scorching 96° F outside during a picnic in Temecula when Dr. Maia Uli started to feel ill.

The Sharp Rees-Stealy Medical Group OBGYN had just helped decorate a birthday party for the daughter of one of the nurses she works with. First, there was a sense of uneasiness, followed by jitters and clamminess, then an excruciating headache. When the telltale heart palpitations began, Dr. Uli knew she was in for another "episode."

What followed instead was a struggle for survival spanning weeks, a race by Dr. Uli's

Sharp Memorial Hospital medical team to diagnose her mysterious illness, and an early decision by Dr. Uli herself that may have ultimately saved her life.

A fluctuating heart rate for no reason

The episodes began out of nowhere, four years earlier, when Dr. Uli was completing her medical residency in Chicago. Barely 30 years old at the time, she started feeling shortness of breath, a bad headache and heart palpitations while attending a salsa dancing convention.

She went for a full cardiac workup at a nearby hospital. There, doctors found nothing wrong and said she probably felt faint because her body overreacted to some sort of environmental stimulus.

The episodes continued, though rarely. Dr. Uli wasn't too concerned, although the incidences were a little scary. Without warning and without explanation, her heart rate would plunge to around 50 beats per minute, even though her resting heart rate was typically in the 80s and 90s. Exercise, hot weather and even using her hairdryer would trigger the opposite — Dr. Uli's heart rate would soar to over 160 beats per minute.

Oddly, the episodes always lasted about 15 minutes.

'Everything was negative'

Fast-forward to January 2019, when Dr. Uli was now a practicing OBGYN at Sharp Rees-Stealy's medical offices in Rancho Bernardo.

Her episodes would come and go, but she learned to live with them, thinking her body was just extra sensitive. A long-time fitness buff, Dr. Uli was forced to tone down her workouts, as rigorous activity seemed to bring on her symptoms.

One day at work, Dr. Uli felt her heart rate drop distressingly low once again, but it didn't recover after the typical 15 minutes. She called her primary care doctor and requested an order to check her own heartbeat on the clinic's electrocardiogram (EKG). One of the nurses in her office performed the exam, which showed that Dr. Uli's heart was in atrial fibrillation — an abnormal irregular rapid heart rhythm.

Atrial fibrillation (AFib) occurs when the two upper chambers of the heart experience chaotic electrical signals and begin to beat fast, or irregularly. The condition greatly increases the risk of stroke, but typically affects adults in their 60s and older.

Dr. Uli's nurse drove her to Sharp Memorial Hospital, where a panel of sophisticated cardiac tests and a chest X-ray revealed nothing physically wrong with her heart.

"Everything was negative. Everything," Dr. Uli says. "It was odd, but I'm a doctor, and I know how accurate these tests are."

'I'm going to Sharp'

Eight months later, on that hot September day in Temecula, Dr. Uli wasn't too surprised when her symptoms began. But when a 90-minute rest inside an air-conditioned building didn't help, she decided it was time to head back to University Heights, where she lived with her husband, Jess Bradshaw.

Luckily, her mom had accompanied her to the party, so Dr. Uli climbed into the passenger seat and the two set off south together.

About 30 minutes into the drive, just as they were nearing her clinic in Rancho Bernardo, Dr. Uli began vomiting uncontrollably. She gurgled while trying to breathe, a concerning sign that her lungs were filling with fluid. Dr. Uli's mother took the freeway off-ramp and drove straight to the nearest urgent care, where a doctor called for an ambulance.

In the ambulance, Dr. Uli made a decision that may have saved her life. The medics insisted on taking her to the closest hospital, but Dr. Uli, still somewhat conscious, demanded she go to Sharp Memorial Hospital.

"I said, 'Get me out. I'm going to Sharp'," she recalls. "I told them I would make my mom drive me the extra distance. I had to sign a waiver that I was going against medical advice, but I did. There was no way I would go anywhere else."

The ambulance ride to Sharp Memorial was a blur, but Dr. Uli vaguely remembers fighting against a machine intended to keep her airway from collapsing. She needed to breathe, desperately.

Then, for the next four days, everything went black.

A novel way to save lives

Before 2010, CPR was the best option that emergency doctors had of saving lives. Then a handful of Sharp Memorial Hospital emergency doctors began to wonder whether a special heart-lung bypass machine traditionally used during planned surgeries in the operating room could buy some of their emergency patients more time.

The complex device — called an extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) machine — functions as an artificial heart and lungs by removing blood from the body, circulating it through the device and returning it to the body, oxygenated.

ECMO had not previously been used in any Emergency Department in the world. But, the doctors brought the device down to the emergency department, learned how to use it from a team of highly specialized ECMO nurses, and ultimately saved their first life with the device — a man in cardiac arrest. Those doctors then developed the first-ever formal training program to teach physicians how to initiate ECMO during cardiac arrest. Today, Sharp Memorial emergency doctors travel all over the world training physicians on its use.

Dr. Maia Uli with her husband, Jess Bradshaw, while unconscious and on ECMO in the intensive care unit at Sharp Memorial Hospital.

Running out of options

Dr. Uli didn't know any of this when she demanded the medics take her to Sharp Memorial. As a Sharp employee, she simply trusted their quality of care.

At the hospital, doctors struggled to intubate Dr. Uli; her airway was so blocked with fluid that it was nearly impossible to place a breathing tube down her throat to deliver oxygen to her lungs. When he arrived at Sharp Memorial, her husband, Jess, said doctors told him his wife was in respiratory failure.

In the intensive care unit, Dr. Uli's condition didn't improve. She "coded," or went into cardiac arrest, and had to be resuscitated with CPR by the medical team. At this point, doctors began to consider ECMO.

"She was getting sicker and sicker," says Dr. Andrew Eads, an emergency doctor at Sharp Memorial. "We were running out of options."

ECMO is not for everyone. To be considered, patients must meet multiple criteria that give them the best chance of handling the stress of the device, which involves inserting garden-hose-sized tubes into major blood vessels in the neck and groin. Age is a major factor, as well as a patient's general health before their medical emergency and the likelihood they'll return to a normal life.

The ECMO program at Sharp has been around for 30 years, thanks largely to the philanthropic efforts from the Sharp HealthCare Foundation.

“These machines are an absolute necessity to have,” says Dr. Joe Bellezzo, one of the emergency doctors who founded the Emergency Department ECMO Program at Sharp Memorial Hospital. “Currently we have eight machines, purchased with philanthropic funds. These donations and support from our community help ensure we can continue providing life-saving care.”

Dr. Eads said Dr. Uli was a good candidate for ECMO, but the medical team had to move fast. While setting up the machine at her bedside, Dr. Uli coded again. Once she was resuscitated a second time, they successfully connected the device within minutes.

The next day, while Dr. Uli was still unconscious, still fighting for life, and still connected to the ECMO machine, an echocardiogram revealed some terrifying news. Her ejection fraction, which measures how much blood the heart pumps out of the body with each beat, was only 10% - damage likely caused by her two cardiac arrests.

At only 34 years old, Dr. Uli was in complete heart failure, and doctors still had no idea what was making her so sick.

Part 2: Read the conclusion of Dr. Uli's story.

For the news media: To talk with Dr. Maia Uli or her Sharp Memorial Hospital medical team for an upcoming story, contact Erica Carlson, senior public relations specialist, at erica.carlson@sharp.com.

The Sharp Health News Team are content authors who write and produce stories about Sharp HealthCare and its hospitals, clinics, medical groups and health plan.

Dr. Maia Uli is an OBGYN with Sharp Rees-Stealy Medical Group and affiliated with Sharp Memorial Hospital and Sharp Mary Birch Hospital for Women & Newborns.

Dr. Andrew Eads is an emergency physician affiliated with Sharp Memorial Hospital.

Joe Bellezzo, MD is a board member of the Sharp HealthCare Foundation.

Our weekly email brings you the latest health tips, recipes and stories.